KEESLER AIR FORCE BASE, Miss. -- Most pilots are trained to avoid storms, but the pilots of the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron are the only ones in the Department of Defense whose job is to fly through them.

“Our job is to safely and effectively accomplish the tasking by leading the crew through a storm mission—whether it’s a tropical system, a winter storm, or an atmospheric river,” said Maj. Alex Boykin, an instructor pilot with the 53rd WRS.

Although the unit, better known as the Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunters, operates year-round, they are best known for hurricane flights. Those missions often begin long before a storm is named. When a tropical low forms, crews conduct “invest” flights at altitudes as low as 500 feet above the ocean to determine whether the disturbance has the winds necessary to become a tropical system. Once a system develops, the National Hurricane Center tasks “fix” missions, which send aircraft directly through the eyewall to collect wind, pressure and structural data—critical information that helps forecasters predict strength and track.

During winter, winter storm and atmospheric river missions can take crews from the Atlantic to across the Pacific, sampling long corridors of concentrated moisture. The data improves rainfall forecasts, helps prevent flooding and supports water resource planning for millions of people.

When hurricane season arrives, pilots’ work becomes far more intense when flying directly into violent storms.

“Getting to the storm is the same as any other flight,” Boykin said. “But once you’re in it, the flying is quite different. Sometimes it takes both pilots on the controls working together to keep the aircraft stable.”

He recalled flying through Hurricane Milton, a Category 5 storm. “It was rapidly intensifying,” Boykin said. “As we started to penetrate the eyewall, it felt like slamming into a wall. I had both hands on the controls while the other pilot worked the throttles just to keep us level. I’ve never felt anything like that in any other flying that I’ve done.”

The mission, he said, is about more than collecting data. “Too many people think that if they’re outside the cone, they’re safe,” Boykin said. “But the cone only shows the possible track of the storm’s center. Hurricanes can span hundreds of miles, so you can still be in danger even if you’re outside the cone.”

Hurricane Hunter Maj. Boykin

U.S. Air Force Maj. Alex Boykin, instructor pilot with the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, sketches Hurricane Sally at Keesler Air Force Base, Miss., Aug. 03, 2025. Boykin, who flew through the 2020 storm, drew the system’s spiral bands and eyewall structure to illustrate the challenges Hurricane Hunters face when navigating aircraft through severe weather. The artwork highlights how crews combine aviation skills, meteorological data and experience to safely complete missions that provide critical information to forecasters. (U.S. Air Force photo by Senior Airman Shelby Jessee)

1 of 2

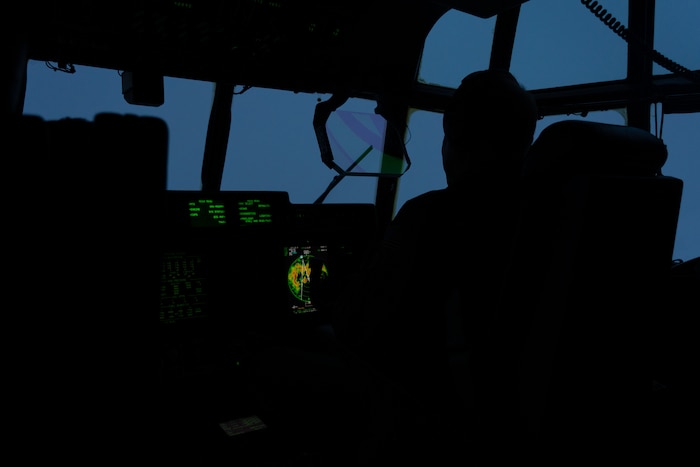

Hurricane Hunters fly Hurricane Sally

Members of the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron fly into Hurricane Sally to gather data on September 14, 2020, in the Gulf of Mexico. The Hurricane Hunters fly through tropical systems to gather weather data that they provide to the National Hurricane Center for their use in updating the storm forecast warnings. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Shelton Sherrill)

2 of 2

To emphasize the point, Boykin sketched the track of Hurricane Sally, which made landfall near Gulf Shores, Alabama, on Sept. 16, 2020, as a Category 2 storm. The slow-moving hurricane caused widespread flooding and wind damage across coastal Alabama and the Florida Panhandle.

He showed how the storm itself stretched well beyond the forecast cone. The cone only reflects the projected path of the storm’s center, not its overall size or impact. “Most people around Pensacola thought they were going to be fine because they were on the edge of the cone,” he said. “But Sally was about 90 miles wide, yet the cone was only about 60 miles wide. Pensacola was always going to get hit—even if it wasn’t a direct hit, the area was still going to get hurricane-force winds and flooding rains. People were not ready because they didn’t understand what the cone was telling them.”

For Maj. Will Simmons, also a 53rd WRS instructor pilot, combines two lifelong interests. “I started flying in seventh grade and earned my pilot certificate in high school,” Simmons said. “Through flying I realized I really liked the weather side of aviation, so I got a degree in meteorology from Mississippi State. That’s when I first learned about the Hurricane Hunters.”

Simmons, a Mississippi native who has been with the squadron since 2015, said it is rewarding to see the impact of their work. “It’s a great feeling knowing the data we collect directly impacts forecasts,” he said. “Ultimately, that information saves lives.”

Boykin said that’s what keeps him motivated. “We’re operating a giant machine in a giant weather system,” he said. “If the information we bring back helps people prepare, that’s why we’re doing it.”

Whether crossing the Pacific or flying through the eye of a hurricane, the Hurricane Hunters provide information that helps safeguard lives and property.

For information on joining the Air Force Reserve and pilot career opportunities, visit https://www.airforce.com/careers/aviation-and-flight/pilot or contact an officer accessions recruiter.